The Innovation Journey: A Conversation with Lucie Howell

'If we're going to share these ideas and stories, we need to recognize that it is important to tell the truth. We need to recognize that nuance matters, and the kids are smart enough to understand nuance."

Lucie Howell is the Chief Learning Officer of The Henry Ford, a museum that explores the American experience of innovation, ingenuity and resourcefulness.

"God bless all elementary teachers out there because they are amazing at creating these interdisciplinary experiences where students just move naturally from developing one set of skills to the other."

Mentioned in this Podcast

The Transcript

Erika Block: I'm Erika Block and I'm here with Lucie Howell, who's the chief learning officer of The Henry Ford. What is a Chief Learning Officer?

Lucie Howell: Well, that's a really good question and I'm still figuring that out. For the most part, my responsibility really is to drive our learning strategy and help support the organization and the institution...really figure out what educational platform do we want to build and tell our stories from, and how can we do that in the most innovative but most relevant ways possible?

I think we're also looking at ensuring that we do them with best-practice ideas in mind. So, it's part of my responsibility to kind of know what the current educational, philosophies that we should be activating as a learning institution, and really sharing those with the organization such that we're able to share our stories and have them help people learn, develop and grow as guests -- to whatever degree the guest is comfortable and engaging. So, for some of those guests, it's maybe come to the museum and have a fun time. Right? For others, we actually embed this into the learning experience.

For example, we work with Detroit Public Schools Community District. We have fourth and fifth-grade field trips and we've actually developed a curriculum where the students learn before they come to the museum, and come to The Village. And then they have a learning experience at The Village as part of a field trip day, and then they have followups. That's really deep, embedded learning. And so my responsibility, and my team's responsibility, is to figure that out from a very low-level touch to a really integrated learning experience.

Erika Block: So, let’s go back and define the word platform, because we use that in so many different ways. So, is curriculum a platform? Or what is a platform when you talk about that?

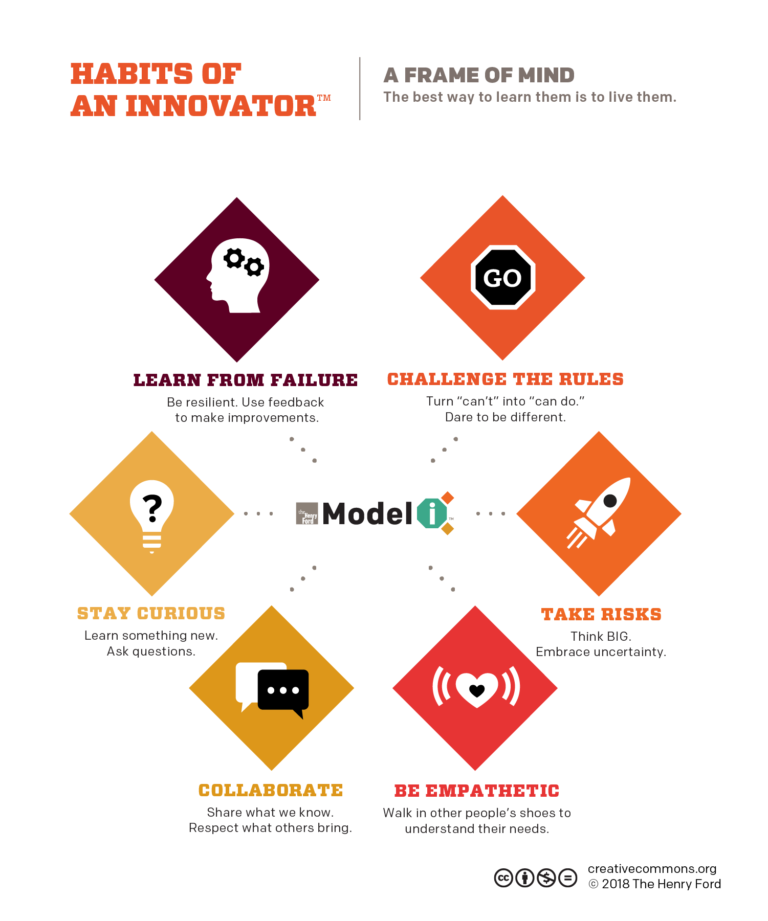

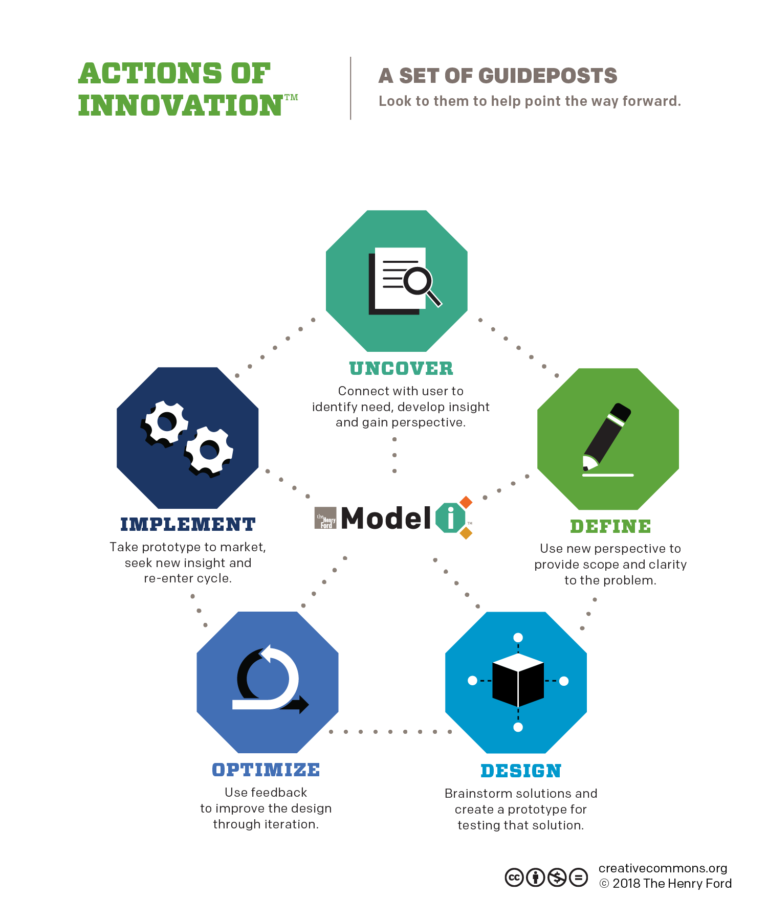

Lucie Howell: I guess, and maybe this is the engineer in me, when I think of platforms, I think of it sort of as a launch point. So, our launch point has really developed, as an innovation learning framework -- which is really a language that has been pulled from our objects and stories. We call it the Model I Innovation Learning Framework, and we talk about the habits of an innovator and the actions of innovation. And these are habits that we see again and again and again in the stories of innovators that we have across the venues and the actions that we see individual inventors and innovators showcase, or teams of inventors and innovators showcase, across their stories. One of the things we've learned through this process is that every innovation journey is unique. So, you'll notice we don't talk about the innovation process. We talk about an innovation journey. And the reason is because of that uniqueness. You can have the same inventor or the same team of inventors, who exhibit the same habits, but for a new invention they'll actually take a slightly different, innovation path. So, each journey is unique. But what we see again and again are these actions reappear and the habits that those people activate in that journey come up again and again. That’s allowed us to have this language where we can tell the story of Rosa Parks, alongside the story of Thomas Edison, alongside the story of George Washington Carver -- and it creates this lovely kind of connective tissue for the stories that could, at first glance, feel sort of isolated and individual.

Erika Block: What are some of the connective tissues or threads?

Lucie Howell: George Washington Carver was a scientist in the agricultural field, and he worked a lot on optimizing different seeds. So, you can see that story kind of resonate with a Thomas Edison story -- optimizing the invention of that tungsten material and his team doing that. With Rosa Parks, there was a lot of taking risks and challenging the rules. Those are some of the habits of an innovator that we talk about. And again, in order to invent one new thing once a week -- which was the goal that Edison set his team -- you have to take risks and challenge rules to be able to do that.

And that's, I think, one of things that the learning landscape teaches us -- that it's so much easier to make connections across stories when there is a common language. And this framework really gives us that common language to help others make, create connective tissues.

There were six habits that we've highlighted, and by the way, we don't think that these are the only habits of any innovator, but these are the ones we see again and again and again across our stories. And now you're going to test me. Let's see if I can remember them. So, there's learning from failure, which is probably my favorite one. There is: take risks, challenge the rules, stay curious, be empathetic, and collaborate. Nice one.

And then the actions of innovation -- there are five of those: uncover, define. design, optimize, and implement. And the actions sound to me, as an engineer, very much like the engineering design process. But I think what I've learned through the stories from The Henry Ford is...it's actually...the power is when these two things come together to tell those journey stories.

As an engineer, I was always taught to use the engineering design process and, you know, it was cyclic -- or as a scientist to use the inquiry process that’s sort of very linear and research-based. But what I've learned is that no person follows it. Or, no group of people follows a particular trajectory...that they take a journey and they experience these steps along the way, and they activate these different habits.

The other thing that's really powerful about this tool is we can now tell each one of the stories that we have using this language, but we can also help people in their own innovation journeys. So, if you are on an innovation journey -- and it can be something as simple as your New Year's resolution being you want to manage your finances at home better -- you're going to create a system where you manage them a little bit better. You can actually think about where am I in my innovation journey? Use those steps, and then recognize the habits you might normally engage with at the step. And if you have hit a wall -- you can't solve that particular part of the problem -- actually activate a different set of habits. So, you might be at the design phase and you're always very good at being empathetic, but you forget to stay curious. Just these will help remind you: “Oh, maybe I need to practice that habit a bit more.”

Erika Block: It's another set of tools to do this. I want to talk about the nature of interdisciplinary thinking and the cross-pollination of experiences and ideas and disciplines which we've touched on here. I want to read a quote from something that you wrote. I saw a blog for Michigan Future and you said, “As you can tell, I think about learning a lot as an engineer by head, and an educator by heart. I care about us all losing out on our collective human potential because our society has set up systems that, without meaning to, limit how our innovative potential is recognized and encouraged.”

That’s very much in sync with what you've just discussed. I'll give you an example of conversations I recently had with somebody who said you can have the most interesting and innovative technology and even a tremendous market for it, but in the end it comes down to the people and the systems they build and the stories they can tell to get it out. And you could argue that people and organizations are harder than technology and pure science. And so it seems it's something that’'s embedded in this.

Lucie Howell: Yes, I think it is embedded. I think, probably the biggest frustration that I experienced as an educator, is...and it started when I was teaching science. I remember one of my kids turned to me and said, “Ms. Howell, you need to stop teaching me math because you're my science teacher. Can you get on with the science, please? And not teach me math?”

Erika Block: Eighth grader?

Lucie Howell: Well, yes! And that to me really demonstrated that we had done something to education. We had created these siloed buckets that young people

really, genuinely thought: “You know, when I am in a math class, I do math for no other reason than to do math because I'm in a math class. And then I go to my science class and the same job happens there.”

What's fascinating to me is when you think of Pre-K kids or elementary kids, that learning experience is completely intertwined and totally interdisciplinary. God bless all elementary teachers out there because they are amazing at creating these interdisciplinary experiences where students just move naturally from developing one set of skills to the other. Right? We then move kids into kind of middle school and high school, and then college, and at each step we create bigger and more narrow fields and bigger and bigger silos, and create even harder and harder walls to break down.

And then, at the end of all those experiences, we put them out into the world of work and then go and say, “Go be interdisciplinary! Go be cross-functional.” And then we wonder why they don't know how to...why teamwork is so -- it can be challenging for many people when everything they’ve done up until that point in time has been measured -- that success is measured on the individual’s ability and they're actually put on assessment mechanisms that have them competing as individuals; against one another. Yet, we want them to then learn the skills of teamwork. That, you know, the rising tide lifts all boats.

One of my other things about young people is: It isn't what you tell them. It's what they see that matters. So, you can say to a kid, time and time again, that learning from failure, for example, is a really important part of life. That you really need to learn from failure. But if that kid sees that Dad come home from work, and that Dad is feeling failure at work and he's worried about the risks of that in terms of that work -- then that kid is learning that we're basically telling them a lie. Right? And I think that's part of my frustration, too. If we're going to share these ideas and stories, we need to recognize that it is important to tell the truth. We need to recognize that nuance matters, and the kids are smart enough to understand nuance. So, that young man is smart enough to understand that it's okay to learn from failure. It is okay to take risks. But you might need to address the risks that you're taking or the failures you're willing to make, dependent upon the situations you're in, right?

Nuance matters. And I think all too often we have a tendency to try and simplify everything down to, you know, that five words or...and I think human beings are smarter than that. I certainly know the kids I've worked with a smarter than that,

Erika Block: How do you sustain that? I completely agree with you, but I also -- and this is a conversation we have a lot: people don't pay attention enough to get the nuance. We're moving so fast. We don't have time. We're overloaded. We have too many responsibilities. There's a zillion reasons why. And this extends to work. It extends to our families. It extends to our politics. Nuances. Really, it requires attention. It requires time.

Lucie Howell: Yes, it does. This one's a hard one because you have to recognize the realities that we live in. Right? But I also think you have to hold people accountable. What was really being said in there is that we're all a little bit lazy, right? And, I don't know if you want something...it isn't meant to be easy to get it. Right? It's the things that are really important in life are the things you work for...and the things you work for are things that take patience and they take time. And we have developed a tendency to this idea of: it should just come easy. And if it isn't coming easy -- If I don't feel comfortable and okay...then someone did something wrong. And we look around for who did something wrong? Why is this experience that I'm having one that's challenging me? Right? I shouldn't have to have this. I shouldn't have to sit in this discomfort.” But I'm going to make an argument, which is you never learn anything new unless you're made to feel slightly uncomfortable about your current state of learning.

Erika Block: Yes.

Lucie Howell: There's a reason why you go on and learn a new math technique. It's because the ones that you have don't quite work for the new situation. Therefore, you're uncomfortable enough that you've got to go and do the next thing because that will help make it easier. That, I think, is true for everything in life. And one of the things...and I think this is a challenge for adults, honestly: As a Gen Xer, I have been taught that my job was to always solve everybody's problems for them and that I shouldn't ever have anyone in my space that should feel uncomfortable at any point in time. Like my job is to go and fix it, whether it's me as the mom, me as a teacher, frankly me as a bs -- that discomfort in other people is not a good thing. And I’m meant to go in and fix it.

Well, first of all who am I to be the one to know what is the right fix for every single person? There's a lot of hubris in that! And the second thing is...by doing that, I'm actually not allowing other people to grow and develop, and persevere, and learn that it's important to wait long enough and actually listen and pay attention because nuance matters. I almost feel like we have created our own monsters.

I would argue that maybe rather than us saying things like: “We don't have time. Things move fast. People don't have the attention spans.” Maybe by doing that, we're making people comfortable with not bothering to be patient and listening. Maybe we need to be starting to change that narrative and start saying, actually, nuance matters. And you might want to spend ten more extra minutes on this, really thinking and playing with it, rather than ignoring it. And I know that is a really uncomfortable thing but, you know, I said, “New learning doesn't take place unless you're made to feel uncomfortable with where you're currently at.”

Erika Block: Yes. There's actually research that says you have to be uncomfortable or pushed in order for it to really resonate with you. So, I agree with you -- by the way, I'm sort of playing Devil's advocate with all of this -- I'm going to go back to the same article where you cited a metaphor from Lou Glazer who's the Director of Michigan Future. And, I think you say he nailed what your work in education has been all about. He said that the education systems we're working with now were designed to prepare people for the career ladders of the past -- and not the career rock faces of today and the future, ...which is just lovely.

Lucie Howell: I couldn't agree with you more.

Erika Block: Yes. So, what you're talking about was with the increased rate of change in our work society that has derived from technological advancement. We need to develop talented people who are prepared to be flexible and adaptable, both in the work they're doing, and in their expectations of how and where that work will come from. In short, we need to provide learning experiences that arm our young people with the tools to move forward without always having a specific and clear endpoint or correct outcome in mind. And then you say, so what does that look, sound and feel like? And that's actually my question to you. What does that look, sound, and feel like?

Lucie Howell: It looks, sounds, and feels uncomfortable, right? And I think that, for me, is sort of a big part of it. What's interesting is I've always accepted change is the norm. I was talking with a very close friend of mine just recently -- I think I realized that my experiences in life have made me more accepting that change is just normal. In fact, for me, things staying the same feels very abnormal. I moved around a lot as a child. The one thing I could rely on is that every year looked different. I was probably living in a different house. I was probably going to a different school. I may well have been in a different country -- and so the only thing I could rely on was that change was completely normal. And so learning to be flexible and adaptable to that change, but kind of ground myself and who I was, was a really important thing for me. I hadn't realized until recently how that makes me slightly askew to a lot of people that I have the privilege of working with or living with.

And, I think, what we are looking at for young people moving forward is that they are going to need to be okay with change in a way that their grandparents didn't need to be. And even their parents. I think that parents are experiencing it, but even they won't need to be. And so we've got to be able to arm them with the tools of how to manage change and how you actually embrace it. And you know, people ask me, how do you do that? And one of the things I always say is the notion that things stay the same is actually a false narrative anyway. So all of us have the tools to adapt and be flexible because change has occurred in all of our lives all of the time. It's just that I happen to be way more comfortable with it than most. And I guess what you hear me wanting...is to ensure that those young people I know are going to experience -- just feel -- the same level of comfort. So, when they know change is happening, it isn't something that is scary. It isn't something to fear. It's something to kind of embrace. To have the wherewithal of saying, I've got all of these tools in my toolbox. I've got it. I know change is going to happen. Change is going to be slightly uncomfortable, but I've actually got tools to manage that discomfort, channel that discomfort, and use it and learn and develop and grow.

Erika Block: It sounds like you were able to a large degree to develop those tools because you were experiencing change every year when you moved. And so you developed good strategies for when you went into a new school; when you went into a new community. And so that was a learning experience. I would say that I grew up in a house where entrepreneurship, and starting new things and taking risks, was a big part of dinner table conversations. And watching my father, specifically, cycle from being: business going well to doing really poorly. And that enables me to adapt and take risks as an entrepreneur that a lot of people can't. Not very many people have similar situations. So, how do you build learning experiences that come from outside of the lived everyday experiences that we had growing up that can help folks get to this place.

Lucie Howell: Oh! Well, this is my favorite conversation! So, I think for me, project-based learning -- problem-based learning -- is just the key to it. Actually setting young people challenges where the adult in the room doesn't even know what the answer is going to look, sound, and feel like, and they're on the journey with those young people. It's very interesting when you do that. It makes educators very uncomfortable. Teachers like to feel...we were measured on our classroom control and our classroom management. And now more what I'm advocating for is that you’re not, in a sense, managing the experience. I think, for me, classroom management is about facilitating that experience in a safe and rich way, rather than ensuring the successful outcome of that experience. Right? I have seen what happens to kids when they make the sudden realization that their teacher doesn't know what the right answer is, and they go through, you know, a first stage...shock! Second stage: fear. And then the third phase is empowerment.

Wow! I could actually come up and share something with my teacher, or my parent, or the adult -- the person who's meant to know everything in this space -- and tell them something they didn't know.

And I think that's why I love the Invention Convention work so much -- where you have these young people who have chosen to be at the cutting edge. They're inventing brand new things and they've been given the opportunity -- by their educators, by their schools, or by their home -- to just go and be as creative as possible, pushed to the cutting edge of imagination and they feel safe If it doesn't go right, I've learned something from it, and I'll go onto my next invention, or I'll go into something new. And, you know, watching the confidence that comes with that is incredible. I guess for me, that then goes back to this: preparing a talent pipeline for those rock faces.

The more experiences like that you can give young people, the more they will know and understand how to tackle that rock face. The last thing we should do is create, set, truly artificial safe learning environments where kids don't stumble and fall, and then set them at the bottom of a rock face that is their career. Right? That, to me, is a huge disservice to young people. And you know, as an educator, do I want my kids to stumble and fall and feel frustrations? Is it hard to watch? Absolutely! Of course, I don't want that and, yes, it is hard to watch, but yeah, trust me, I would much rather have it in a safe, controlled, managed environment where the risks they're taking are small -- where the failures they're going to have aren’t catastrophic to their lives, or to their lives of their family.

Erika Block: Yeah.

Lucie Howell: And if we don't do that, but we put them at the bottom of a rock face, which is their career, and then have them experience it later with no tools for how to survive, I think we've not educated our kids properly.

Erika Block: Do you think that happens more often than not right now?

Lucie Howell: Oh...a big sigh. I think for all kinds of reasons that are truly people wanting to do the right thing -- we have created a system that has sanitized learning such that they're not ready for those rock faces.

Erika Block: I know this from people who teach at the university and see students who've been raised with no obstacles in front of them. And all of a sudden, they're on their own and they don't know what to do, and their parents get involved. My partner is a psychotherapist and a lot of the students who come in...it was really the beginning of when mental illness was visible, but there were things that were triggered by this sort of failure to launch because nobody made it hard for them when they were younger, and all of a sudden, boom, they were thrown into something on their own. I want to go back to this notion of no rules, no defined outcome, which I think is super important because it's sort of life…

Lucie Howell: Yes, it is.

Erika Block: I'm going to bring it back to this cross-disciplinary thing. So you know, the first half of my career was making theater, and the work that we did was based on improvisation. And my job as a director was to work with folks to bring the right content and inputs and create this environment where people could explore with no defined outcome other than at some point we were going to have a show about a thing. And that thing, the topic, might change, and it was very hard for traditionally trained performers who were used to working with the script that Shakespeare or some contemporary playwright wrote for them. But building that safe environment and allowing people to go on a journey together where the only rules, you know, the core rules of improvisation are: you don't say no to somebody. It's yes. And if somebody hands you a prompt, you go with it. And that's pretty much the rule. And you don't do anything to hurt anybody. And you have to adapt. And what I've seen -- and I've seen this with people who've moved out of theater who have either improvisational or even just hardcore stage production backgrounds. Because you're used to getting that show up. There's no way you cannot meet your deadline. So, if you have to go fix something with duct tape, or if your sound board is broken...you’d better go find a can for that -- to bang on for that sound effect --- or whatever it is you have to do. You have to do it. You have to adapt. You have to make it work. It's never going to be perfect. The outcome is completely unknown because you're going to be in front of a live audience. So you don't even know what that audience is going to be like. They may be tired. They may be thinking about a failure they just had at work. The people I've seen who move into different arenas -- coming out of that background -- are incredibly flexible and adaptable. I would be interested in hearing if you have any particular examples of a teacher, a classroom, a narrative that a student has experienced around this adaptability and the ability to dive into something without knowing that you have to get to a specific outcome?

Lucie Howell: I do. It's my favorite story to tell. So, I was lucky enough to lead a program, when I was working at Quinnipiac University, that was embedding a project-based learning experience into a science curriculum. And we got to work with. Middle school and high school science teachers...

Erika Block: For people who don't think about it. What's project-based learning?

Lucie Howell: Project-based learning is learning where you are given a project to do, that's team-based and you actually have to work and develop a solution. In this particular case, these were engineering projects. So, the idea was we might have a chemistry high school curriculum and it would be an embedded chemical engineering project that the kids then work on. And the idea is you’ll be given a brief -- just like you would be given at work -- that doesn't have an actual specific solution. And what you have to do as a student is to apply your knowledge, apply your skills, apply your understanding, apply your common sense, and work together as a team to come up with a solution to that project. And so you could think of it as a capstone project -- something like that. The idea for this program was that we would have a classic science curriculum, and we would choose an engineering design project to embed into that curriculum. And the students would, as part of that curriculum, have this project-based learning experience -- and this would be something that, if we embedded it into enough of the science curriculum units, they would experience it two or three times in middle school and then two or three times in high school. Because again, what we know is, a one-shot wonder does not work if you want to develop this kind of muscle memory. You have to practice these habits and actions -- and experience them again and again. So, weirdly, I discovered that high school chemistry teachers really, really struggle with this concept of project-based learning and engineering design processes and curriculum.

And I had this one particular group -- one particular teacher -- who very early on said. “I think this is a ridiculous idea. I'm here because my principal told me that I needed to be here.” It was a year-long project, so we spent some time in the summer and then they had to apply it through the year. This was a big ask and this teacher said it right off the bat to me and she went on to say -- with the rest of our team-- “You know, I teach chemistry. You can't do any engineering and chemistry. That's not a thing.” Well, I kind of looked and smiled and said, “Well, that's lovely, but I happen to be a chemical engineer by degree -- so it's not going to fly with me. So, let's move on from there.

Erika Block: Did she flinch? Did she say anything?

Lucie Howell: Oh, no. I think she just smiled wryly and went away and moaned quite a bit in the corner with the rest of the team about, again, how stupid this whole concept was. So, this team actually went on to create a really interesting project because their curriculum was all about absorption as part of 10th grade chemistry. And actually, the project can they came up with was that students needed to design a diaper that could do a number of different things -- and they had these different resources -- and it was actually a really interesting project. But even though they were actually able to come up with a project -- which was her first thing that wouldn't be possible-- she was still not convinced. So, they go back to the schools and they apply this curriculum, they work with their students and, at the end of the year, the whole cohort of teachers comes back to share what their experiences have been so we can look at doing it again and improve the curriculums that were developed. So, they're in the room and, you know, one of my first questions to them was: We're here to share what we've learned this year. And this one teacher, she puts a hand up -- “I'll show what I'm going to share.” And, you know, I had my head in my hands going, Oh, no...anyone...could we start with anyone? But, “Okay, sure. Share your story with me.” And this is a summation of what she said. She said, “As you all know, I started this year not believing in this at all, but I have to tell you that as the year went on, I've completely changed my opinion. This project changed the way my classroom acted and behaved. And the students changed their perceptions of one another because of it.” And she went on to tell the story of...they’d done this project, -- this curriculum -- and when they got to the project piece, all of her students who were straight A students in chemistry struggled and were getting Ds on this project. And all of her D students, who really struggled with chemistry, just loved the project and were getting A's. And while they were doing the project-based piece of the curriculum, the way that the classic A-grade students started to speak and treat, and act with the students who'd been getting Ds changed completely. And the respect for different perspectives, different skill sets changed how her kids talked to one another, and how she thought of them. So, she's sharing this with me, and I have not got my phone on record or anything! But I will tell you, the hairs on the back of my neck went up. Tears were in my eyes because that's why we should do this.

Erika Block: Wow.

Lucie Howell: It was a good moment.

Erika Block: Yeah. Wow. .

Lucie Howell: There was actually something I wanted to add as you were talking about your experiences with improvisation and the people that you had engaged with. One of the things that came into my head is: watching young people go through frustrations. When they're in the middle of that learning because they don't have the answer -- and because the adults in the room don't have the answer -- they're just waiting for the answer. And one of the things that I would want to make sure we own is: Those emotions are really important and powerful. And letting people actually sit in them and experience them, and not go and fix it for them, is part of what drives people to learn and develop, and grow -- feeling the euphoria then of solving the problem. When someone does it for you, you don't get to experience the low emotions; you don't get to experience the high emotions either. And I think when I use that phrase sanitize, that's what I mean. I think by not creating these spaces where some of the more negative emotions we don't want kids to experience -- we're not then giving them the opportunity to experience the high that comes from that. That nuance, and that patience, and that thing we were talking about earlier gets you to.

Erika Block: And I would even say the aha and the intensity of creativity and discovery -- and the parallel to that -- I can think of hundreds of improv sessions where when I was sitting out as a director, One of my roles was to make sure people were safe, but also know when to throw in a prompt or to stop it. And things would come to a standstill -- not very often, but enough...it would come to...there'd be silence and people would not be sure what to do. And it would've been very easy for me to throw in a new prompt to get things moving or say, “Okay, let's try a different exercise.” And the hardest thing I've done when, the hardest thing everybody had gone through was: “No, we're going to sit with this for five or ten minutes until something happens and not change it.” And you can see almost the sweat starting to form on the brows. And, very often, I don't know if it's the majority of the time, but very often, something incredibly powerful came out of just sitting with it until that happened. And that's the story of -- that's the classic writer’s story. That's the classic scientist story. You sit and you wait. Or you repeat and repeat and repeat, and at some point: boom!

Lucie Howell: Something shifts, something moves and you are able to take it to another level.

Erika Block: But you need patience. I think patience is really key here.

Lucie Howell: Which then brings me to the other thing I was gonna mention. As a teacher, I was taught,my responsibility was to set a question at the beginning of a lesson. Set an objective, take students through a one hour experience, that had them address through various activities -- a visual activity and auditory activity, a kinesthetic activity, some kind of mix -- something that would help them figure out the answer to that question. And then, at the end of it, have some kind of capstone moment where that question gets answered. But it was always to leave the classroom with closure -- to have that question answered. To not leave something hanging in the air. And one of the things I now think, is: that's a false framework.

Erika Block: Because there isn’t an answer?

Lucie Howell: No, because different people get to the answer at different stages. And this idea that, by the end of the lesson, I should have given the answer -- what it actually did, upon reflection, is: kids are smart So what did the smart kids do? They knew that if they just waited an hour, I was going to give them the answer anyway. And if they did it by looking like they were doing all the activities very studiously, I would even feel really good about the fact that that happened. But that's not learning. So, I've come to a point whereI will tell some of the teachers I work with: “It's okay for your kids to leave at the end of that hour without having that question completely answered for themselves.” That's okay.

Erika Block: Thank you, Lucie. This was really thought provoking. I've really enjoyed this conversation and I've learned a lot and I look forward to continuing. So, thank you for taking time to speak with us. But also, for the work that you're doing at The Henry Ford.

Lucie Howell: Thank you for having me. This has been fun.