Climate Change and Thoreau's Profound Data Preservation

Thoreau noticed a lot. So consistently detailed were his seasonal observations, they are now being used by scientists to assess the progression and consequences of climate change — a remarkable testament to the power and persuasiveness of data rigorously collected and preserved.

May 21, 1851. Yesterday I made out the black and white ashes. A double male white ash in Mile's Swamp, and two black ashes with sessile leaflets. A female white ash near railroad, in Stow's land. The white ashes by Mr. Prichard's have no blossoms, at least as yet.

This brief 1860 entry from Henry David Thoreau's massive Journal (1835-1861) is but one example of thousands he made during near-daily, multi-hour jaunts across his native landscape surrounding Concord, Massachusetts.

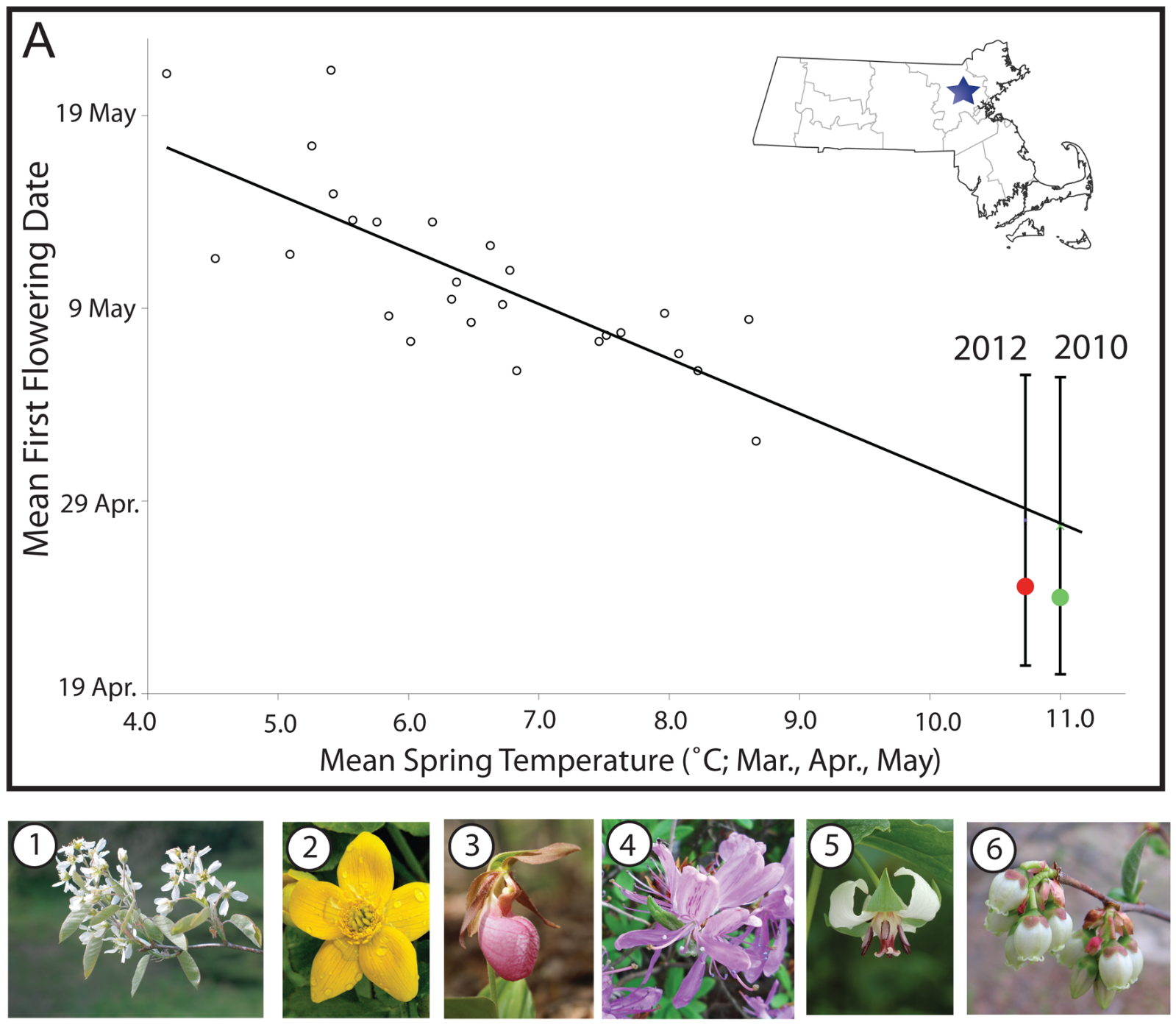

A skilled surveyor and naturalist, Thoreau’s prose, sometimes accompanied by simple ink drawings, is compact and direct — noting with a keen eye and sense of place the annual comings and goings of hundreds of plant species. Beginning in 2003, Richard Primack and his research team at Boston University began observing the blooming patterns of 32 spring-flowering native species from a variety of habitats around Concord.

Using Thoreau’s data set, supplemented by additional data collected by Alfred Hosmer in the late 1800s, the study revealed a dramatic 11-day shift in the arrival of blooming correlating to an average of 3.2 days earlier for each 1°C rise in mean spring temperatures.

For some, this might sound like a pleasing progression with spring arriving ever earlier as greenhouse gases continue to contribute to the increased heating of the planet. And, yes, while an anomalous premature spring in northern climes can feel like cause for a celebration, we know better. As much as this study demonstrates a predictability for certain kinds of natural correlations, the complexities at work in what we prosaically call “climate change,” are monumental and rapidly outpacing all but our most dire of proposed projections.

Strange that data from the mid-nineteenth century should serve us now as a harbinger of potentially catastrophic change, but that is the beauty of data painstakingly gathered and preserved. Through it we are granted a perspective only time can afford us in recognizing patterns and trends that, lacking any serious human response, may soon overwhelm us.